They’re on the lookout for malware that can kill

Our Route 100 Tech Park client Dragos was featured in this Washington Post article on National Security:

The Washington Post | Ellen Nakashima and Aaron Gregg

The cyberthreat hunters had honed their chops at the National Security Agency — the world’s premier electronic spy agency. And last fall, they were analyzing malware samples from around the world when they stumbled across something highly troubling: the first known piece of computer software designed to kill humans.

The researchers, who launched their own firm several years ago, determined that the malicious computer code was created to sabotage a safety system whose sole purpose is to avert fatal accidents. When the system fails, the chance of a deadly accident — in this case, in a petrochemical plant — greatly increases.

“The only purpose of these safety systems is to protect human life,” said Robert M. Lee, co-founder of Dragos, who conducted cyberoperations for the NSA and U.S. Cyber Command from 2011 to 2015. “The only reason to sabotage them is to kill people.”

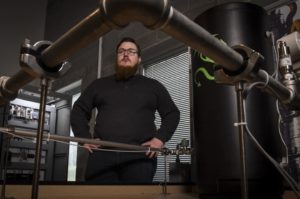

Dragos, based in a techno-hip warehouse in Hanover, Md., is at the forefront of a new line of business for cybersecurity firms. It focuses on industrial control systems — the machines that make oil, gas and electricity flow; pump water; and create chemicals.

A larger and better known firm, FireEye, independently also identified the potentially deadly malware. Yet the obscure start-up is the only company so far to have identified two separate strains of malware that were built to damage or destroy industrial control systems. Several U.S. and Western government agencies have turned to Dragos for analysis and insights on control system attacks.

Lee, 30, and his two Dragos co-founders — Jon Lavender and Justin Cavinee — gained crucial experience at the NSA, which employs a corps of highly skilled cybersecurity operators. But after several years working at the NSA in industrial threat detection, they realized that gathering intelligence on adversaries who are bent on disrupting industrial control systems is one thing. Protecting the systems from those hacks is another.

So Dragos built a software product to help industrial companies detect cyberthreats to their networks and respond to them. Its clients include energy, manufacturing and petrochemical factories in the United States, Europe and Middle East.

In October, Dragos discovered Trisis, a malware that targets a “safety instrumented system,” or a machine whose sole function is to prevent fatal accidents. In a petrochemical plant, for instance, there are machines that operate at very high pressures, and if a valve blows, the pressure or the leak of hazardous materials could kill a human being. But a safety instrumented machine is supposed to shut down the entire system to reduce the risk of a fatal accident.

There has been one known deployment of the Trisis malware — FireEye called it Triton — at a petrochemical plant in Saudi Arabia in August. But a coding error prevented the malware from working as intended, and a potential catastrophe was averted.

As of this week the culprits behind Trisis were still active in the Middle East, Lee said. “It’s reasonable to assume that [what happened last year] is not a one-time event.’’

Though Dragos had some indication of who was responsible, the firm refrained from drawing a conclusion. “It wasn’t cut and dried,” Lee said. Dragos shared the malware with the Department of Homeland Security, but Lee argued against the government seeking to assign blame.

“The best they could do is a well-reasoned guess,” he said. “There’s not the years’ worth of data on this event that would make attribution possible.”

Dragos’s policy of not publicly declaring who it believes to be responsible for a malicious cyber-campaign sets it apart from other cyberthreat intelligence firms.

FireEye, for instance, says that attribution is “critically important” to its customers. To a Persian Gulf oil company, Iranian threats are existential, whereas state election boards would want to know if, for instance, Russians had compromised their systems, said John Hultquist, FireEye’s director of intelligence analysis. Knowing your attackers makes it easier to make the most of limited security budgets, he says.

For Dragos, however, “there’s no value to our customers” in identifying their attackers, Lee said, adding that an inaccurate attribution of responsibility could escalate tensions between states. “Attribution is a political discussion,” he said. “When it comes to our customers’ networks, we want to stay away from the politics and focus on the defense.”

Put simply, he said, “nobody needs to be in anyone’s civilian infrastructure.” If it’s a civilian power plant or manufacturing facility, “we have the full right to kick them out, and we don’t need to know who they are.”

Awareness of threats to industrial control systems soared after the Stuxnet cyberattack on an Iranian nuclear plant was uncovered in 2010. Stuxnet was a computer worm jointly developed by Israel and the United States that caused uranium centrifuges to spin out of control, though the two governments have not publicly acknowledged their role. The operation slowed Iran’s nuclear program but also prompted a cyber arms race, said Sergio Caltagirone, Dragos’s director of threat intelligence.

“Everybody saw that critical infrastructure could be attacked and that they needed to have at least equivalent capabilities in order to maintain parity,” said Caltagirone, who was a pioneer in the NSA’s cyberthreat intelligence work and who later worked as head of analytics and intelligence at Microsoft. “It’s not that it wouldn’t have happened. It would have. But I do believe that it accelerated the trend and was the start of the arms race.”

Today, more than 30 countries have or are developing computer warfare capabilities, and a quartet of nations are considered significant cyber-adversaries of the United States: Russia, China, North Korea and Iran. Though Stuxnet was applied against a military target, the capabilities countries have developed can also be used against civilian systems.

And it is that space — civilian critical infrastructure — that Dragos seeks to protect.

The U.S. government took the unusual step in March of publicly warning that Russia has targeted U.S. critical infrastructure systems, including energy, nuclear and manufacturing sectors, for potential cyber-sabotage. And Iran has targeted critical infrastructure companies in the United States and elsewhere.

The U.S. government’s position is that nations in peacetime should not attack each other’s critical infrastructure — systems that provide crucial services to the public, such as water, electricity and transportation.

For now, the ability to sabotage industrial equipment — as opposed to stealing information — remains a specialized mission available only to the most highly skilled, best-funded hacking groups. That generally means government-funded groups, though that is expected to change.

Dragos recently has identified five nation-state groups outside the United States that are actively targeting industrial systems. In keeping with its policy, the firm is not naming them.

“In any given year, the information security community usually sees one or two such groups,” Lee said. “In 2017, we saw five. So it’s an extremely worrying trend.”

Lee has been watching the threat develop since 2010. At an NSA site in Germany, he was among the first to help the agency map the foreign cyberthreats facing the military’s critical infrastructure and U.S. industrial systems, including worms such as Stuxnet. The NSA didn’t have an industrial control system lab accessible there, he said, so Lee ordered his own equipment on eBay, set it up in his house and at night practiced hacking into it.

He later was posted to U.S. Cyber Command, where he conducted offensive operations. He left CyberCom in 2015, and a year later, with close colleagues, formed Dragos. They received $1.2 million in seed money from DataTribe, a Maryland start-up incubator focused on companies that use spy technology.

They got a further $9 million from AllegisCyber, a Silicon Valley venture fund, and Energy Impact Partners, a New York venture fund created by energy companies, and an additional $1 million from DataTribe. Their open office space features a mini gas pipeline and electric grid. There, Dragos staff, many of them former NSA operators like Lee, discuss technical analyses over beer and pizza and unwind by throwing darts and playing table tennis.

Companies are willing to share their incident data with Dragos because the firm provides security in return, Lee said. As a result, he said, “I have more access to the industrial threat landscape today at Dragos than my entire time at the NSA.”